1. Rumors of Gold

The year was 1851, and the hills of California buzzed with one word: "Gold."

ProspectorsA person who searches for mineral deposits (like gold) from all over the world rushed west—on horseback, in wagons, and on foot, hoping to scoop fortune straight out of the rivers.

Among them was Elena Morales, an eleven-year-old girl traveling with her father from New Mexico. They rode for weeks through dry valleys and over steep passes until they reached a narrow, twisting stream the miners called Eureka Creek.

Tents dotted the banks, and every morning the sound of metal pans scraping against gravel echoed through the canyon.

Elena stared at the cold, rushing water. "Papá, how will we know where to look?"

Her father smiled. "Most people think it's luck," he said. "But gold follows rules—just like any other rock."

2. Reading the River

At dawn, Elena and her father walked along the creek. Her father didn't start digging right away. Instead, he watched the water.

"See how the river bends there?" he asked, pointing to a wide curve. "The water slows on the inside of the bend and speeds up on the outside. Heavy things like gold can't float. They sink where the current is slow."

They scrambled down to the inner curve of the bend, where sand and gravel had piled up in a crescent shape.

"Gold doesn't just appear anywhere," he said. "It starts in veinsA long, narrow band of mineral that fills a crack in rock—long cracks inside quartzA hard, common mineral (often white or clear) that can host gold rock, high in the hills. Rain and rivers wear those rocks down. That's erosionThe process of moving rock and soil from one place to another (by water, wind, or ice). The pieces wash downstream and settle where the water lets them rest. That's depositionWhen sediments stop moving and are dropped in a new place."

Elena ran her fingers through the wet gravel. "So if we learn to read the river…"

"…we learn where the gold likes to hide," her father finished.

3. Fool's Gold and Real Gold

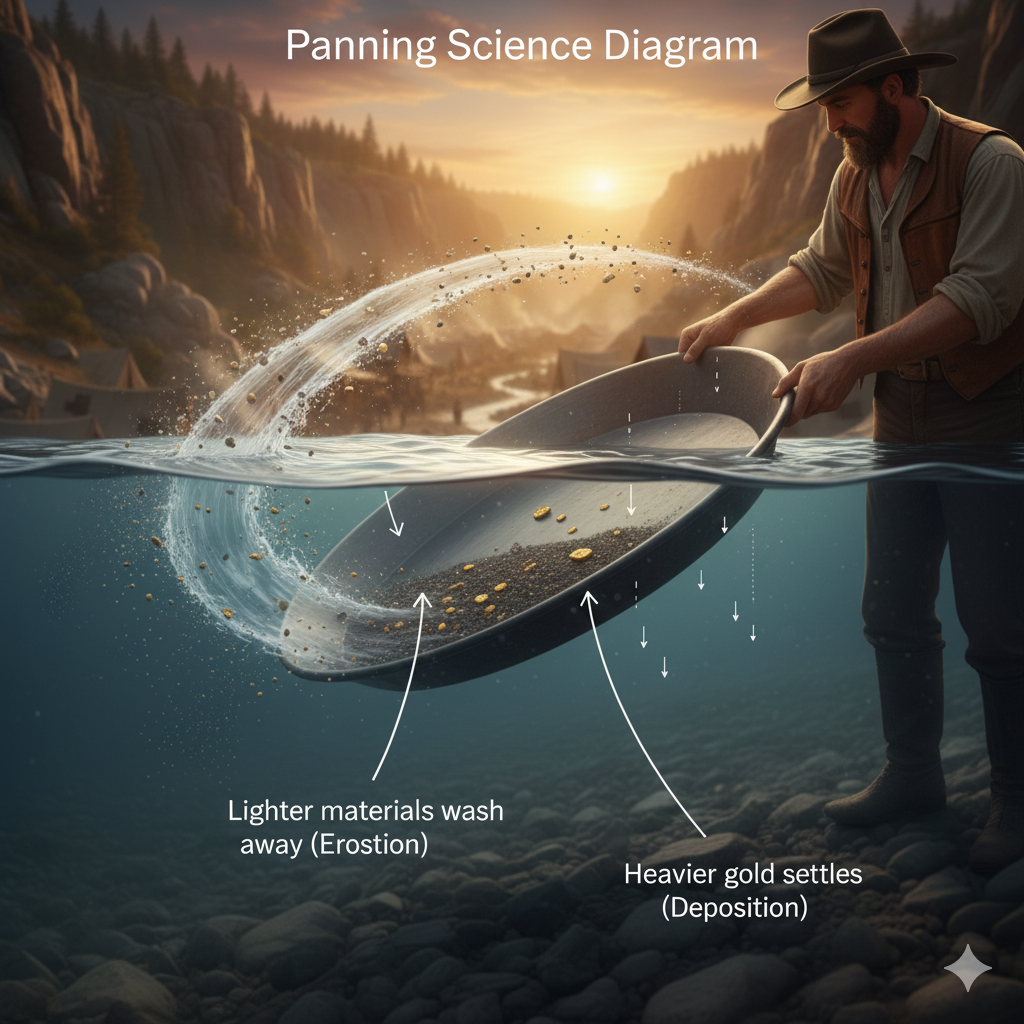

They filled their metal pan with sand and small stones from the inside of the bend. Her father set the pan in shallow water and showed Elena how to swirl and tilt it.

"Gold is very denseHow much "stuff" (mass) is packed into a certain space—heavy for its size = high density," he explained. "That means it's heavier than the other mineralsA natural, nonliving solid with a specific chemical makeup and structure here. When we swirl the water, the lighter sand and pebbles get washed away. The heavy stuff—like gold—stays at the bottom."

As Elena moved the pan, tiny sparkles appeared.

"Look!" she gasped. "We're rich!"

Her father chuckled. "Not so fast. That might be fool's goldFool's Gold (Pyrite): A shiny, gold-colored mineral that looks like real gold but isn't—pyrite. It shines, but it won't pay for a loaf of bread."

He picked up a flake with a wet fingertip and pressed it gently. Pyrite crumbled. Real gold would bend.

"Gold is soft and bends like a tiny metal leaf," he said. "Pyrite breaks like glass."

Elena tried again—this time more carefully. Slowly, the black sand and light grains washed away, leaving a few tiny, bright, yellow specks in the corner of the pan.

Her heart thumped. "Papá… this one bends."

He smiled. "Then we've found the real thing."

4. The Secret of the Quartz Vein

As the days passed, most miners at Eureka Creek grew frustrated. They dug everywhere at random, hoping for a miracle. Many gave up and moved on.

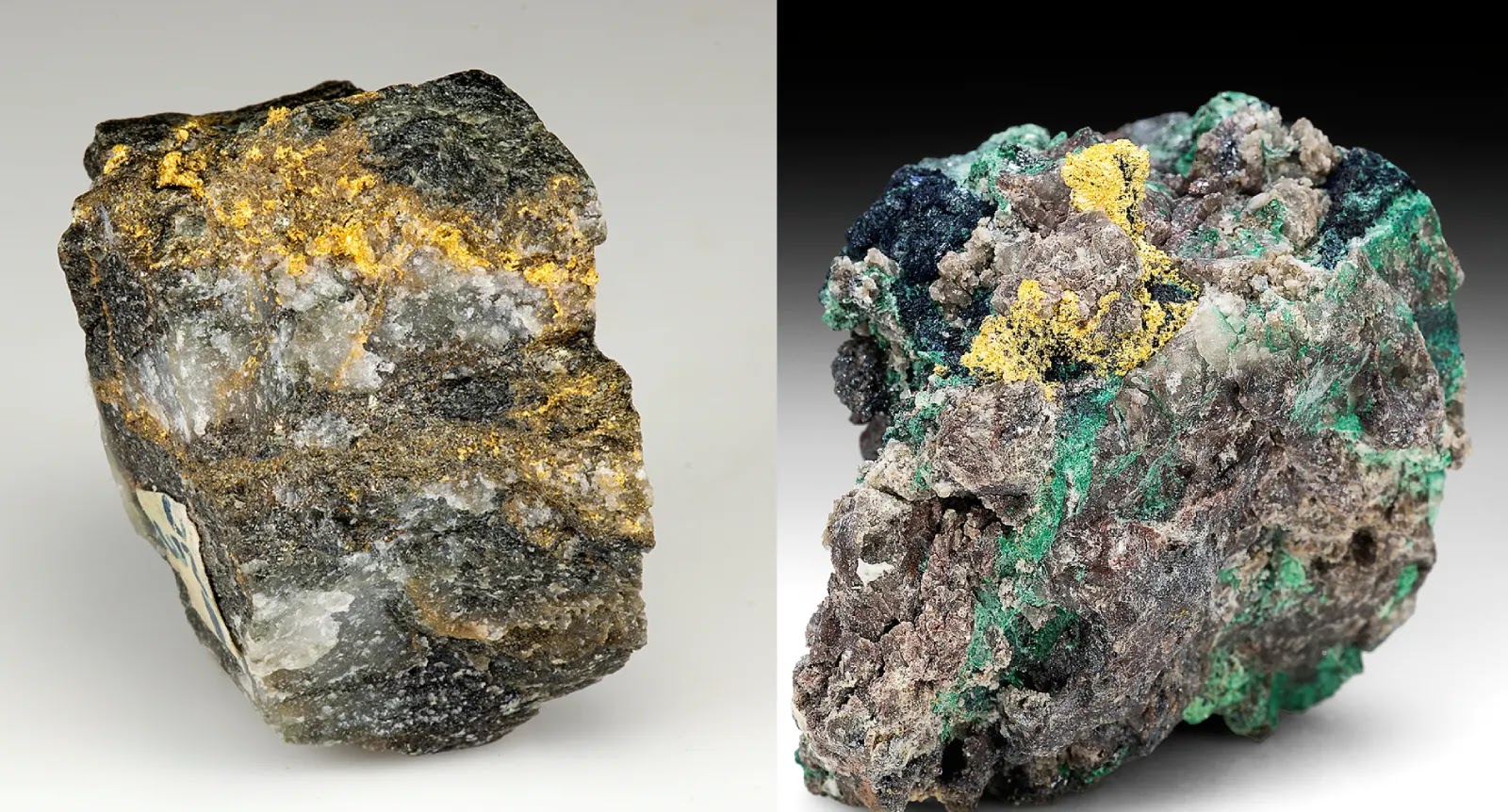

But Elena watched the rocks as much as the water. One afternoon she noticed something strange in the canyon wall above the creek—a pale white stripe cutting through darker rock like a scar.

"Papá," she called, "is that… quartz?"

They climbed carefully toward it. Up close, the veinA long, narrow band of mineral that fills a crack in rock glittered with milky white crystals. In some tiny cracks, she saw faint, threadlike streaks of yellow.

"Gold likes to grow inside quartz," her father said quietly. "This is where our flakes started their journey."

They chipped at the rock with a hammer and chisel, collecting broken pieces of quartz. Back at the creek, they crushed the rock and panned the powder.

This time, when the swirling water washed away the lighter grains, more gold appeared—not just flakes, but small, flat nuggetsA small lump of valuable metal found in nature.

Word spread quickly: "They hit a pocket! Morales found a vein!"

But when other miners rushed toward their spot, Elena's father shook his head. "There's enough creek for everyone," he said. "We'll share what we've learned, not just what we've found."

He showed them how to look for quartz veins, inner bends, and heavy black sands—clues only careful observers would notice.

5. More Than Gold

Weeks turned into months. Elena's family never struck it rich—but they found enough gold dust and small nuggets to buy a little plot of land near the creek, a mule, and warm clothes for the winter.

On their last night in the tent, Elena listened to the burble of Eureka Creek and thought about her journey.

Gold, she realized, wasn't magic. It was science—minerals forming deep underground, erosion carrying them downstream, deposition tucking them into quiet corners of the riverbed, and density helping them sink to the very bottom of her pan.

She looked at the tiny leather pouch of gold dust. "This isn't the only treasure we found," she said to her father. "We learned how the Earth works."

He smiled. "That's the one treasure no one can take from you."

And as the stars shone over the California hills, Eureka Creek kept whispering to the rocks:

Heavy things sink.

Rivers remember.

Look closely, and you will understand.

📚 Vocabulary

💬 Discussion Questions

🔬 Mini Experiment: Density Panning in a Bowl

Goal: Model how density helps separate "gold" from lighter sediment.

You Need:

- A wide bowl or pan

- Water

- Sand or fine dirt

- A few heavier objects (like small metal beads, screws, or pebbles)

- A few lighter objects (like bits of plastic, dry rice, or foam pieces)

Steps:

- Put sand/dirt in the bowl.

- Add the heavy objects and lighter objects, mix them in.

- Fill with water just above the mixture.

- Gently swirl and tilt the bowl, like a gold pan.

- Watch: Lighter materials move and float away more easily. Heavier pieces slide to the bottom edge of the bowl.

Lesson: Just like gold, objects with greater density tend to settle at the bottom when you swirl water—this is how panning works in real rivers.

📸 Real Photos from California's Gold Mining History

Gold Mining in San Gabriel Canyon (1932)

Even 80 years after the original Gold Rush of 1849, people were still searching for gold in California's mountains! This photo from 1932 shows a miner using the same panning technique that Elena learned in our story. He's swirling water and gravel in a metal pan, letting the heavy gold settle to the bottom while lighter rocks wash away. San Gabriel Canyon, near Los Angeles, had small amounts of gold in its streams. During the Great Depression in the 1930s, when many people didn't have jobs, some returned to gold panning hoping to find enough to buy food and supplies. This miner is using the power of density—just like Elena did nearly 100 years earlier!

From Ore to Gold Bar (Modern Mining)

Today, gold mining looks very different from Elena's time! Modern miners don't just pan for gold flakes in streams. Instead, they dig deep underground or into mountainsides to find gold ore—rock that contains tiny particles of gold mixed with other minerals. After crushing the ore into powder, they use chemicals and heat to separate the pure gold from everything else. This photo shows molten (melted) gold being poured into molds to create gold bars. The gold is heated to over 1,900 degrees Fahrenheit until it becomes a glowing liquid! When it cools and hardens, it forms shiny gold bars that can weigh up to 27 pounds each. Even though the tools have changed, miners still rely on understanding mineral properties—just like Elena's father taught her.

Gold in Quartz Rock (Natural Formation)

This is exactly what Elena and her father discovered in the canyon wall! You can see shiny yellow gold growing right inside white quartz rock. Deep underground, hot water carrying dissolved minerals flows through cracks in rocks. When the water cools down, minerals like gold and quartz crystallize and stick to the walls of the crack, forming a vein. Gold loves to grow alongside quartz because they often form under similar conditions of heat and pressure. The white mineral is quartz, one of the most common minerals on Earth. The gold appears as bright yellow streaks, threads, or nuggets wedged into the quartz. Miners call this "high-grade ore" because you can actually see the gold with your eyes instead of needing special equipment to find it!

Gold Prospecting Today

Believe it or not, people still pan for gold today—over 175 years after the California Gold Rush! Modern prospectors use metal detectors, GPS devices, and geology maps to find promising locations. But when they get to the stream, they still use the same basic technique Elena learned: swirling a pan to let density do the work. Some people do it as a hobby on weekends, while others make a living finding gold in remote streams and rivers. They follow the same clues Elena's father taught: look for the inside bends of rivers, check for black sand (which is also heavy), and search areas below where quartz veins reach the surface. Though most won't get rich, they enjoy being outdoors, learning about geology, and occasionally finding a small nugget or some gold dust. The science of gold panning hasn't changed—it's still all about density!